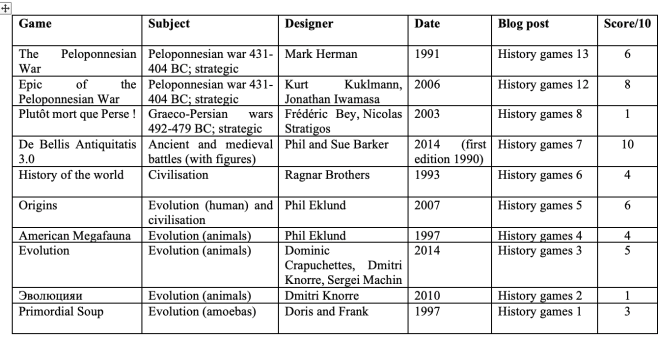

In my last history games blog I wrote about how Epic of the Peloponnesian War is my favourite strategic game among the games of that war (6 strategic, 3 operational and 4 tactical) that I played between last June and this February. My second favourite is Peloponnesian War (PW).

Kurt Kuklmann and Jonathan Iwamasa are the designers of Epic. The only thing I know about them is that I love their game.

Mark Herman is the designer of PW. He is the Thomas Edison or Leonardo da Vinci of board wargames, he has invented so many things. I’ll hold back from writing about his most influential invention, the CDG (Card Driven Game), until I play one.

PW is a solo game, with a flowchart – a ‘bot’ – that decides what the non-player does. Your aim as the player is to end the game quickly. What’s special about the game is that if you take the lead but do not secure victory, you are liable to be switched to command the other, losing side.

I like wargames for the stories they generate. For these stories to come into being each side has to try to win: even when I play with others, though, the pleasure I get depends only marginally on whether I do in fact win. I play a lot of games on my own, and don’t feel the need of bots. Moreover the side-switching mechanism feels contrived; I didn’t use it. So the thing that is special about this game wasn’t important for me.

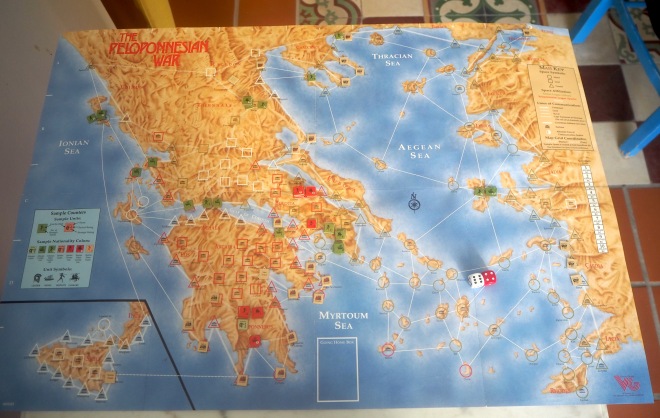

PW has spaces rather than hexes. There are only three troop types: hoplites, cavalry (representing all light troops) and naval. The movement and combat systems are simple. It plays fast, with 3-year turns. After each force moves you roll an ‘auguries’ dice with a chance of not being allowed to move again. The game also has money, but these dice rolls seem to be the main way it ensures that forces’ levels of activity are not ahistorically high.

I took PW to Greece last August and played it twice, on a succession of hot nights, in Nafpactos and then in Koroni – both of them named spaces in the game.

The first time I played I let the bots run both sides. I can’t find my notes, but I remember that Sparta won, in 7 turns. Lots of Athenian cities in the Aegean and Ionia rebelled, sapping Athens’s will to fight, and the Athenian bot did not pay attention to bringing them back under control.

The second time I played with two sentient players – that is, I did the best I could with both sides. There was more activity and the sides spent more money. Athens won in 4 turns, which took me three evenings to play – five or six hours altogether, maybe. I found this version better.

Afterwards I found on line a variant by Morgane Gouyon-Rety: in the auguries dice roll 123 you act freely, 45 you obey the bot, 6 you can’t move any more. This could be the ideal compromise. It would work solo or with two players.

The look of the game is nothing special. The counters, in particular, are unengaging. To be remembered that it is, that these objects are, nearly 30 years old.

(It was reissued last year; the map looks to be the same, but the counters look livelier.)

As a game, it plays smoothly and is satisfying.

From a historical point of view I’m not comfortable with the three year turns. Maybe it’s true that about as much happens in each three year period in this game as happened historically. But I’d rather have yearly turns with troops marching out in spring and coming home for the winter, coupled with a stronger constraint on how much you can do each turn.

Herman says in his designer’s notes that the side-switching mechanism was inspired by the career of Alcibiades, who fought for Athens, Sparta, Persia and then Athens again. OK, but Alcibiades chose to switch sides, for advantage of some kind. The game makes you do it, to your detriment.

I think this mechanism scrambles up all sense of who you, the player, represent.

The way I played the game, either the bot (first game) or me as the player (second game) would seem to represent “the Athenian/Spartan high command”, something more unified than existed in reality. That’s why I’d like to try Gouyon-Rety’s variant, which I think depicts a tension between the player (a sort of rational leadership group) and the bot (a representation of the emotional tides to which leaders had to pay attention).

I was going to give PW seven points because of its merits as a playable game, but these doubts about historicity at both levels (the results it produces, and the mechanisms by which it produces them) have led me to drop the score to six.

I had the idea of a single post reviewing the six strategic games. I got daunted by the idea of writing it and wrote nothing for months. I kept on playing games in chronological order. I am now up to Alexander’s invasion of the Persian empire and have built up a backlog of reviews.

It’s April 2020, the time of corona. Game playing is what I need. When we got locked down I resolved on a policy of two reviews for each new playing. This makes two, I’m going to play the Samnite Wars scenario in Richard Berg’s Rise of the Roman Republic. Not a light game, if I remember well when I played the first Punic war scenario with my friend the Admiral. See you again when that game is done! Keep safe.