(Brussels, 2015)

(Brussels, 2015)

For Netherlandish reasons I’ve been reading a biography of Philip II, king of Spain in the sixteenth century, by Robert Kamen.

Philip’s deprecators called him the Spider of the Escorial. Kamen isn’t a deprecator but he shows that Philip spent much time at the Escorial palace, which he had built outside Madrid; that he liked to do business in writing; and that his handwriting meets the dictionary definition of spidery: consisting of thin, dark, bending lines, like a spider’s legs.

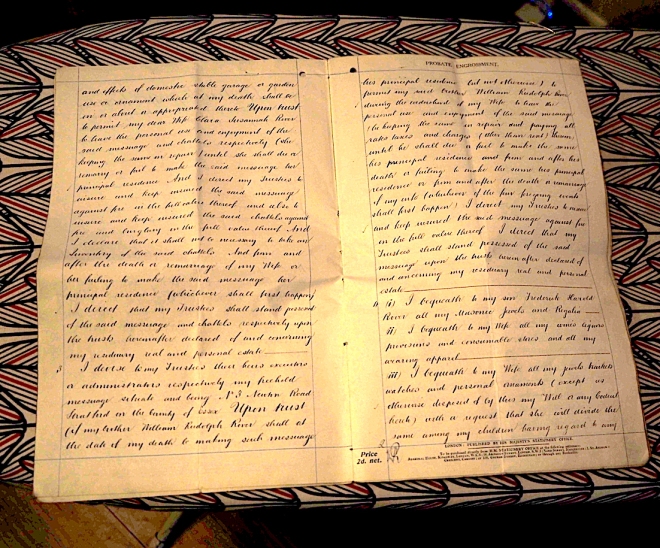

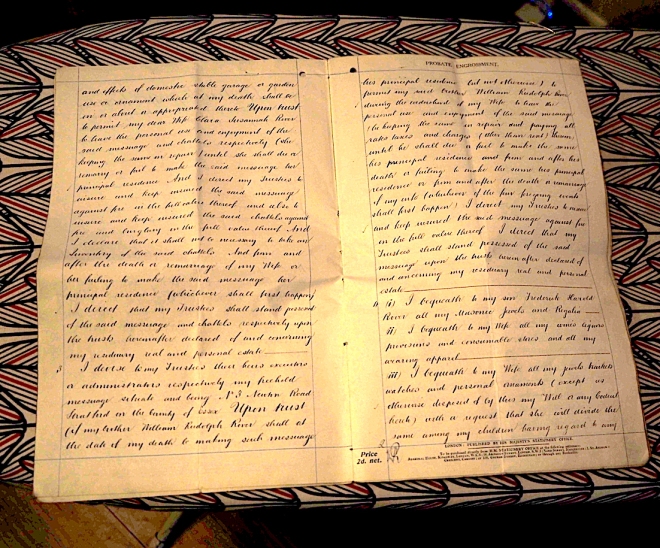

(I suspect, though, that then and later, everyone wrote like that. Here, for example, are pages from the will of Travelling Companion’s great-grandfather.

I suspect that no-one wrote in rounded letters like this:

(Leo ich liebe Dich– Leo I love you – Ahrweiler, Germany, 2015);

(Leo ich liebe Dich– Leo I love you – Ahrweiler, Germany, 2015);

(La révolution ça se passe pas que sur les écrans– the revolution is not only televised – Brussels, Belgium, 2017),

(La révolution ça se passe pas que sur les écrans– the revolution is not only televised – Brussels, Belgium, 2017),

or in square letters like this:

(La manera de hacer es ser– the way to do is to be – Oviedo, Spain, 2016)

(La manera de hacer es ser– the way to do is to be – Oviedo, Spain, 2016)

(Fuck rules let’s art – Levkas, Greece, 2017)

(Fuck rules let’s art – Levkas, Greece, 2017)

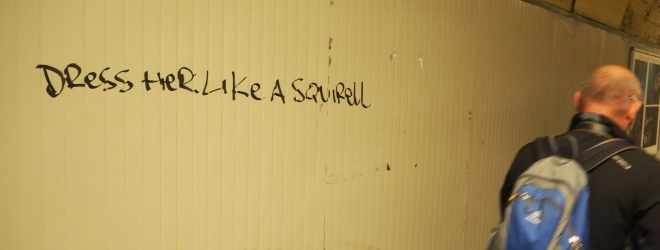

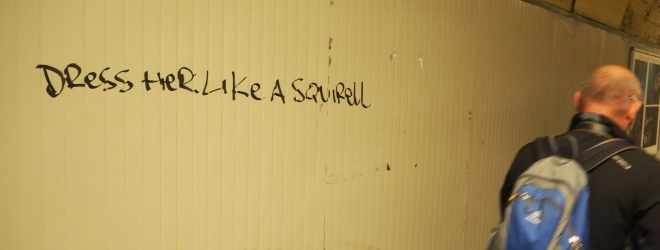

(Dress her like a squirell – Manarola, Italy, 2016)

(Dress her like a squirell – Manarola, Italy, 2016)

(I am not Kate but I look like her– Orsha, Belarus, 2018)).

(I am not Kate but I look like her– Orsha, Belarus, 2018)).

I’m digressing.

I think Philip worked this way, in writing, out of shyness. According to Kamen, “Unlike other European monarchs, he preferred information to be given not verbally but in written form. Council meetings, for instance, were normally held without him: ‘He never attends the discussions of his councillors,’ ambassadors observed in the first decades of his reign…. When Vàzquez [his secretary] in 1576 suggested that in several matters it might be quicker to conduct business orally with his ministers, he conceded that it might be a good idea. ‘But,’ he said, ‘my experience of nearly thirty-three years dealing with affairs, is that it would be onerous to have to listen to them and afterwards see them to make a reply, and much worse with those who speak a lot.’”

At least, Philip wrote fast. “One night in April 1578 he had just finished a quantity of papers for his secretary at 9.30 p.m. when he was handed yet another report. He continued what he was writing and then scribbled his protest: ‘Now they’ve given me another file from you. I have neither the time nor the head to look at it so I won’t open it until tomorrow. It’s past ten and I haven’t had dinner and my table is full of papers for tomorrow; I can’t manage any more for now.’ In that half an hour his hand wrote exactly 468 words.”

Nevertheless his centralised system, the many matters touching his broad empire that had to wait for his written decision, made things slow. Granvelle, the viceroy of Naples, “quoted a previous viceroy as saying that ‘if one had to wait for death he would like it to come from Spain, for then it would never come’”.

(At A-level I studied 17th-century European history. I have remembered for forty years a quote I learned then, If death came from Spain, we would all be immortal. Is this a different translation of the same remark, or was it a cliché? Googling, I find yet another version attributed to Granvelle himself: If death came from Spain, I should be immortal. I suspect that Kamen is more reliable than Mr Google or the source used by my teenage self.)

For Philip, writing was thinking. “The king’s annotations on correspondence were a manner of thinking aloud, rather than a deliberate baring of feelings. He did not invite an answer. ‘There is no need to reply,’ he scribbled once to Vàzquez. ‘I am writing only to relax from weighty matters with you.’

For my part, face to face is how I like decisions to be come to and to be communicated.

(The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, for which I’ve worked since March, has six sites in five countries. I am still learning the skills you need to work “face to face” when meetings are by videoconference.)

But I like to write too.

I write in my diary for ten minutes most mornings, about anything, about buses, about Brexit. When I don’t write it, I feel things getting mixed up. For me, writing certainly is thinking.

(For example, the other day I made another attempt to divine how Brexit might come out. It was only when I was writing down my conclusion that a general election in the autumn was likely that I realised that Mr Johnson or Mr Hunt could alternatively offer Parliament No Deal subject to a Second Referendum.)

No thought is properly thought till you’ve tried to write it down, I find. Often, writing it down, I discover that my pretty thought has holes in it.

(Andrés Neuman, How to travel without seeing, about a book tour in Latin America: A journal supposedly reflects our thoughts, experiences and emotions. Not at all. It creates them. If we didn’t write, reality would disappear from our minds. Our eyes would remain empty.)

When I was 14 I would sneak into my father’s study to get onto his typewriter. Later I got my own typewriter and learnt to touch type. I’m not sure why I did this, perhaps to contribute to a school wargaming magazine. Typing is the only manual skill I have and it has served me well. In my diary I typically write forty words a minute.

But handwriting is slower than typing. At the start of last year, over a few days, I wrote my diary longhand. I liked it physically, but my word count fell to twenty-five a minute. And, writing a diary is freer than writing for work. For work I think I’ve done well if I manage thirteen words a minute – and that’s typing. For work the Spider was managing sixteen, longhand. Not bad.

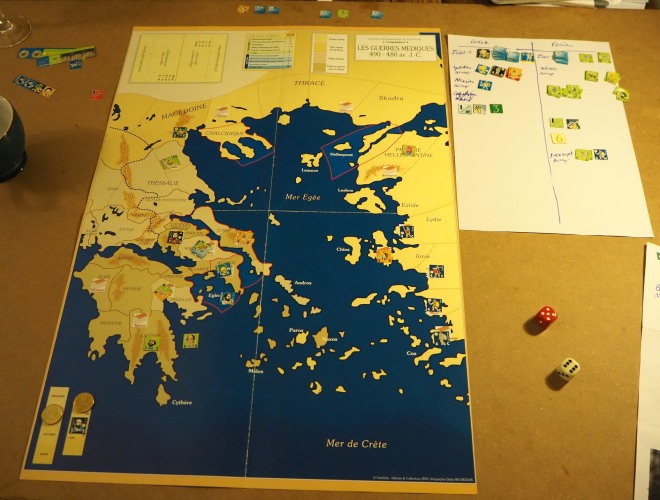

(Bilbao, Spain, 2016)

(Bilbao, Spain, 2016)

PS I recently read Ann Patchett’s collection of essays, This is the story of a happy marriage. Until her novel Bel Canto made it big, she made her living writing 800 or 900 word articles for magazines. I’ve since been feeling inferior because my blogs boil down to half that. I’ve made this one longer. It wanders.

(Cycling home, outskirts of Alkmaar, Thursday)

(Cycling home, outskirts of Alkmaar, Thursday)

Ijmuiden

Ijmuiden North Shields

North Shields

(Brussels, 2015)

(Brussels, 2015)

(Leo ich liebe Dich– Leo I love you – Ahrweiler, Germany, 2015);

(Leo ich liebe Dich– Leo I love you – Ahrweiler, Germany, 2015); (La révolution ça se passe pas que sur les écrans– the revolution is not only televised – Brussels, Belgium, 2017),

(La révolution ça se passe pas que sur les écrans– the revolution is not only televised – Brussels, Belgium, 2017), (La manera de hacer es ser– the way to do is to be – Oviedo, Spain, 2016)

(La manera de hacer es ser– the way to do is to be – Oviedo, Spain, 2016) (Fuck rules let’s art – Levkas, Greece, 2017)

(Fuck rules let’s art – Levkas, Greece, 2017) (Dress her like a squirell – Manarola, Italy, 2016)

(Dress her like a squirell – Manarola, Italy, 2016) (I am not Kate but I look like her– Orsha, Belarus, 2018)).

(I am not Kate but I look like her– Orsha, Belarus, 2018)). (Bilbao, Spain, 2016)

(Bilbao, Spain, 2016)